Multi-Tantra

Once upon a time…..an artist reached home tired after a long day’s work. The artist had a daughter and her name was Manya.

Manya was a two year old lovely little thing. She liked her father making pictures at home. She used to sit with him and ask a lot of question.

On that particular day, though tired he was, the artist decided to paint the picture of a dog. Manya came around and sat next to the artist.

He took the brush and started painting a white dog with black patches on his body. The dog in the picture looked leftwards.

Then the artist painted a gramophone. It was looking just the opposite direction.

Manya asked her father, “Papa, are they crossed? Why do they look away?”

The artist smiled and said: “Manya, my daughter….Once upon a time…they used to look at each other. Then some people started going around the town saying that the dog was only listening to His Masters Voice. The dog was a fiercely independent being. He got really irritated and then on whenever he saw the gramophone he started looking away from it….”

“And then, Papa…..what happened?”

The artist was making a story out of a pictorial situation. Now he really needed to invent a conclusion for it. He looked at Manya…..

Moral: If you have a story, you will have to tell it for your future generations.

The origin of ‘One Hundred and Eight Small Stories’, the exhibition project of small scale works of Manjunath Kamath could be traced back to Manya’s demand to listen stories from her father. She has been watching Manjunath doing his paper works at home and she developed an intense affinity for the images that he created. She wanted to know why her father selected certain images that made her curious.

In his paintings Manjunath employs a technique of fragmented narration. Fragmented images, which are identifiable within the cultural making of a nation and the individual, are painted against vast flat surfaces. The viewer could read in and out of these fragments in order to create feasible, palatable and socially affirmative narratives, though the artist continuously tries to invert the logic of an affirmative narration.

For Manya, his dear little daughter, Manjunath assumes the role of a traditional story teller, who uses pictures for effective communication. He supplements the pictures with words and gestures. He becomes a performer in front of his charmed daughter and these small picture squares become a scroll that unwinds itself in a magical pace revealing never ending stories that at times defy the logic of grand narratives in their quirky perfection.

Story telling is an interactive performance art form, which demands an unwritten agreement between the teller and the audience. Through this unwritten pact of engagement, story telling becomes a co-creative process. What is personal in the story teller is made into a public act where the doors of mutual interpretational possibilities get opened up. It is a uniquely human process, where love and sharing cement the bonding between the story teller and the audience.

Manjunath has primarily only one audience in this pure act of sharing; Manya. Later/now in the space of exhibition, the number of audience increases. The performance of the artist becomes gestural in the space of exhibition as his quirky images are left alone to perform themselves. Manya is in a privileged position as she has the chance to see and listen. But the two year old girl, unlike the culturally conditioned exhibition goers, has to make an effort to encode the stories as stories, images as images and narratives as narratives. Meanwhile, the conditioned viewers are forced to decode the images to make them fit into their prescribed narrative understandings. The co-creative process of Manjunath’s story telling through his small scale paintings functions from two different planes; privileging and disprivileging of the viewer within the unwritten pact of engagement.

Now Manjunath has to tell a story for Manya.

“Once upon a time there was a blue God who liked red pillows.”

“Why a God is always blue and pillows are red in your stories, Papa?” Manya asks.

Instead of giving an answer, Manjunath keeps smiling. Manya looks at his face and the picture of the blue God. She seems to be trying to digest the blueness of the God and the redness of the pillow.

“God was interested in the red pillow. But the prince who had been turned into a banana by a curse was the owner of the pillow. One day the God demanded the pillow from the banana prince. Then the prince told him that he would not part with the pillow as it was given to him by his father. The God became angry and he sent out heat waves to the banana. As he felt hot he removed his skin and slept on the red pillow….”

Moral: Absurd stories as well as stories with logic would invite questions from children. Be careful.

“The story can go on,” Manjunath says. “In many ways…in many forms…in many shapes,” he adds.

However, the artist is not away from logic. In South India the icons of Gods are mostly done in blue. Krishna is referred to as the Blue God. Manjunath likes Krishna. He is always there at his studio. And the icons of the Gods are covered with red silk. Memories of a ritualistic past and the daily reminders from kitsch.

Stories often start with “Once upon a time…..” and mostly end with “Then they lived happily ever after.”

Through allegories (here absurdity itself as allegory) social norms are conveyed to a young audience, who first encode and then decode the moral implications of the stories. In each phase of life, stories from the past come back to awaken one to consciousness. The co-creative process of story telling becomes a virtual continuum.

‘Once upon a time’ sets the tone of the story. It serves two purposes: One casting the listener away from the real time. Two, providing the viewer with a space of detachment from where he/she could see the truth value of what is being narrated.

For a child of Manya’s age, moving away from the real time is a fun voyage. Perhaps, a child constantly converts the real time into fantasy time. If so how does a child imagine a God or a king, when the father tells her, “once upon a time there was a god/king.” Children who are not invested with a vast visual vocabulary might envision a king from the verbal narrative provided to them and they could even imagine a king in the form of a beggar, who perhaps is familiar to them, with attributes that corresponds to a king; like beard, a head gear, a staff, sharp eyes, long hair, flamboyant/decadent dress etc.

For a child, truth value of an allegory comes from indoctrination of ideas through repeated narration. They are receptive of repetitive narratives. What Manjunath does here is a subversion of indoctrination. His defilement of the logic of grand narratives (even those of the quasi-allegories that he himself creates) and his attempt to leave them open and never ending, then functions as an advanced aesthetic strategy to destabilize the structures of linguistic patterns ingrained in the consciousness of the general art viewer. He says, “This is not even a Foucault.”

Moral: Don’t get carried away by grand theories on art. There is something very simple that looks very complex in art.

The statement of the artist, ‘This is not even a Foucault’ reminds the reader of Michel Foucault’s linguistic deconstruction using Rene Magritte’s painting ‘This is not a Pipe.’ In the art his+story Foucault’s formulation, this is not a pipe has gained an allegorical status by now. Manjunath, in his stories keep inventing allegories through the absurd interpretation of stories that have already become the collective cultural capital of a population.

Allegories have a special quality. They renew themselves to the context of its reading. They look like containing eternal truisms. Whether it is Aesop’s Fables, Panchatantra or John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress one could see morals and lessons applicable in ordinary human situations. For example:

Once upon a time, there was a software engineer who used to develop programs on his Pentium machine, sitting under a tree on the banks of a river.

He used to earn his bread by selling those programs in the Sunday market. One day, while he was working, his machine tumbled off the table and fell in the river. Encouraged by the Panchatantra story of his childhood (the woodcutter and the axe), he started praying to the River Goddess. The River Goddess wanted to test him and so appeared only after one month of rigorous prayers. The engineer told her that he had lost his computer in the river. As usual, the Goddess wanted to test his honesty.She showed him a match box and asked, "Is this your computer?" Disappointed by the Goddess' lack of computer awareness, the engineer replied, "No."She next showed him a pocket-sized calculator and asked if that was his. Annoyed, the engineer said "No, not at all!!" Finally, she came up with his own Pentium machine and asked if it was his. The engineer, left with no option, sighed and said "Yes." The River Goddess was happy with his honesty. She was about to give him all three items, but before she could make the offer, the engineer asked her,"Don't you know that you're supposed to show me some better computers before bringing up my own?"The River Goddess, angered at this, replied, "I know that, you stupid idiot! The first two things I showed you were the Trillennium and the Billennium, the latest computers from IBM!" So saying, she disappeared with the Pentium!!!Moral: If you're not up-to-date with technology trends, it is better keep your mouth shut and let people think you're a genius, than to open your mouth and reveal u r dumb!!! *

Manjunath enjoys creating allegories in his paintings and even in the performative act of telling stories out of these paintings. He profusely adopts and refashions the images and projects them into a new field of image permutations and combinations. This process of collecting and rearranging images from the vast cultural storage is like curating an archive. Manjunath calls his images as archival images; the archive that he has created in his own large scale paintings.

“What is an archive, Papa?” asks Manya.

This question cannot come from a two year old toddler. But in story there cannot be any counter questions. It is an area for suspending disbeliefs willingly.

“An archive is a renewable and ever growing collection of information. It refers to a collection of records, and also refers to the location in which these records are kept. Archives are made up of records which have been created during the course of an individual or organization's life. In general an archive consists of records which have been selected for permanent or long-term preservation.”

Manjunath actively debates the issue of preservation of images. For him images are to be used in multiple ways to create new situations which obviously would demystify the sanctity attributed to the preserved images. One could see the image of a clown cap and a politician’s cap sitting on the top of a table without disturbing eachother’s existence. But the very silence of these images generate a smile. Archival images loose their sanctity at various levels in Manjunath’s works.

Moral: Don’t discount a child because Child is the father of man.

Politics and mundane situations play a major role in the production of images and stories in Manjunath’s works. As usual he uses his inverse logic to interpret them as stories frozen in frames.

During the time of Taliban unrest in Afghanistan, one of the Indian writers** proposed an easy solution for all the problems in that country.

“In a male dominated society like Afghanistan, women do all the menial works. These Taliban soldiers who wage war during day time must be going home for food and sex during nights. The best way to solve the Taliban problem is to send the Afghan women to warfronts. When the Taliban males come to know what is child caring and cooking, they will naturally call back their women from warfronts and mend their ways.”

It is a stretched logic and this kind of logic has its own fun. They apparently look like providing a solution for any problem though a second thought reveals that they are only stretched imaginations. However, they offer a possibility to engage the brains in a different direction. Held against an evading solution, possibility for multiple solutions is always appreciable.

Manjunath’s paintings with stories or stories with paintings, in this way offer many possibilities for finding solutions for any social problems. They look real at one stage, cynical at another and eventually they look like parables that soothe the human mind but actually do not function as a solution.

Tiger and deer drinking water from the same river is an image that emphazises the ultimate expression of co-existence. It is a stretched possibility. Manjunath reformulates the image in a contemporary situation of world politics. Here one finds a cat and mouse, sworn enemies for eons, drinking milk from the same pot. They are in a cartoon situation. They can assume their real selves at any time. This is a moment of temporary reconciliation, espeically when both of them have enough to eat or drink.

“When will they start fighting again, Papa?” asks Manya.

“They will be fighting soon and the rat will make a nose dive into a soft pillow. The cat will get into the gown sleeves of the queen while the rat will try to go up through her frock,” Manjunath says.

Each picture offers a story, whose narrative could begin from anywhere and the more the viewer/artist’s dexterity the better he can take it to all narrative possibilities. Manjunath locates a story while adding qualities to an image. He feels that the moon is so soft that one should be using a pair of scissors with velvet covers for its blades, while cutting the moon into two.

“Why do you want to cut the moon, Papa?” Manya does not ask.

Because in her father’s stories every thing is possible. There is magic in Papa’s stories.

Magic is the art of hiding and revealing. Magical realism is a literary technique to hide and reveal truth in a simulated historical context. Manjunath uses both magic and magical realism in his works.

Animal forms mutate themselves to create a new reality. Static images are animated as if they were moved by some invisible forces. The curio objects placed in glass bottles start moving as if they were in a fun park. A landscape appears itself as a ‘piece’ of landscape on a wall stand. An elephant makes a careful descending through a sloppy platform without knowing that the rope that has been holding him is at the verge of a snap.

Everything is animated in this world of story objects. And the animation is materialized through the placement of images within the pictorial format. Most of them either exit or enter the picture frame from a nowhere. At times, one could see a dog partially within the frame, while its tail is on fire. One could imagine, what would be happening next?

Negation of what is socially accepted makes Manjunath’s works more interesting. The famous HMV dog is seen sitting against the gramophone. He does not want to follow His Master’s Voice. But the gramophone is not challenged. It also turns it face away from the dog. ‘I am not interested to talk to you.’

Moral: All dogs are not interested in listening to His Masters Voice.

The artist follows the child’s logic, though he likes to defy logic altogether.

“What do you do when you are tired, my sweetie?” He asks his daughter.

“I take rest, Papa,” Manya replies.

“What should an ancestral clock do if it is tired?”

“It should take rest, Papa.”

“That’s why in this painting, sweetie, you see the key is taking rest inside the belly of the clock.”

“Papa, what is this balloon doing here?”

“Sweetie, it is tired. It is breaking a wind and unwinding itself.”

Moral: If you are tired, unwind and if possible break a wind.

Manjunath’s world is full of pun and fun. He lampoons the social hypocrisy by painting the middle class aspirations objectified in three piece suits, tiger skin and souvenirs. If you take pride in having a pet Dalmatian or a tiger cub, you can sport even a collar that simulates the skin colour of the pet. Impossibilities are made into possibilities in his quirky world of stories.

The artist envisions a world where communication becomes almost impossible thanks to redundancy of certain things which are commonly in use now.

“What is that, Papa?”

“It is a cow daughter.”

“A cow, what is that?”

“A cow is an animal that gives milk.”

The child identifies milk with a feeding bottle. But it cannot identify a cow. There could be a day, when cows are seen only in pictures. Then what will the artist do?

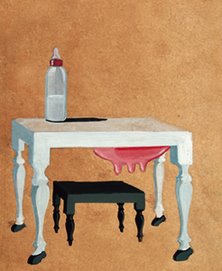

“I paint a cow table. A table with cow legs and an udder fitted underneath it. You may even see a calf in a small table just below the udder.”

Moral: Extinction of word images from the common parlance can bring forth neo-surrealist art.

Manjunath has the last laugh as he paints ants all over the conventional images. They are going to be invaded by ants. It is an insect infested world. They would rule the world one day. The story of apocalypse is told to a little child in subtle terms.

“Who is that man, Papa?” Manya asks.

“He is a saint, baby. Look at him. He has a halo fitted behind his head. It can work as a halo when disciples are around and as a fan when he is attacked by mosquitoes.”

“Papa, will you give me this picture?”

“No my sweetie, it is already booked by an art collector.”

Moral: Children would demand saints as they think saints are like children.

JohnyML, a contemporary of Vatsyayan who wrote Kamasutra, overheard the conversation between Manjunath Kamath and his daughter Manya, and did this text thinking that it would be included in the catalogue of the show titled ‘One Hundred and Eight Stories.’

Once upon a time…..an artist reached home tired after a long day’s work. The artist had a daughter and her name was Manya.

Manya was a two year old lovely little thing. She liked her father making pictures at home. She used to sit with him and ask a lot of question.

On that particular day, though tired he was, the artist decided to paint the picture of a dog. Manya came around and sat next to the artist.

He took the brush and started painting a white dog with black patches on his body. The dog in the picture looked leftwards.

Then the artist painted a gramophone. It was looking just the opposite direction.

Manya asked her father, “Papa, are they crossed? Why do they look away?”

The artist smiled and said: “Manya, my daughter….Once upon a time…they used to look at each other. Then some people started going around the town saying that the dog was only listening to His Masters Voice. The dog was a fiercely independent being. He got really irritated and then on whenever he saw the gramophone he started looking away from it….”

“And then, Papa…..what happened?”

The artist was making a story out of a pictorial situation. Now he really needed to invent a conclusion for it. He looked at Manya…..

Moral: If you have a story, you will have to tell it for your future generations.

The origin of ‘One Hundred and Eight Small Stories’, the exhibition project of small scale works of Manjunath Kamath could be traced back to Manya’s demand to listen stories from her father. She has been watching Manjunath doing his paper works at home and she developed an intense affinity for the images that he created. She wanted to know why her father selected certain images that made her curious.

In his paintings Manjunath employs a technique of fragmented narration. Fragmented images, which are identifiable within the cultural making of a nation and the individual, are painted against vast flat surfaces. The viewer could read in and out of these fragments in order to create feasible, palatable and socially affirmative narratives, though the artist continuously tries to invert the logic of an affirmative narration.

For Manya, his dear little daughter, Manjunath assumes the role of a traditional story teller, who uses pictures for effective communication. He supplements the pictures with words and gestures. He becomes a performer in front of his charmed daughter and these small picture squares become a scroll that unwinds itself in a magical pace revealing never ending stories that at times defy the logic of grand narratives in their quirky perfection.

Story telling is an interactive performance art form, which demands an unwritten agreement between the teller and the audience. Through this unwritten pact of engagement, story telling becomes a co-creative process. What is personal in the story teller is made into a public act where the doors of mutual interpretational possibilities get opened up. It is a uniquely human process, where love and sharing cement the bonding between the story teller and the audience.

Manjunath has primarily only one audience in this pure act of sharing; Manya. Later/now in the space of exhibition, the number of audience increases. The performance of the artist becomes gestural in the space of exhibition as his quirky images are left alone to perform themselves. Manya is in a privileged position as she has the chance to see and listen. But the two year old girl, unlike the culturally conditioned exhibition goers, has to make an effort to encode the stories as stories, images as images and narratives as narratives. Meanwhile, the conditioned viewers are forced to decode the images to make them fit into their prescribed narrative understandings. The co-creative process of Manjunath’s story telling through his small scale paintings functions from two different planes; privileging and disprivileging of the viewer within the unwritten pact of engagement.

Now Manjunath has to tell a story for Manya.

“Once upon a time there was a blue God who liked red pillows.”

“Why a God is always blue and pillows are red in your stories, Papa?” Manya asks.

Instead of giving an answer, Manjunath keeps smiling. Manya looks at his face and the picture of the blue God. She seems to be trying to digest the blueness of the God and the redness of the pillow.

“God was interested in the red pillow. But the prince who had been turned into a banana by a curse was the owner of the pillow. One day the God demanded the pillow from the banana prince. Then the prince told him that he would not part with the pillow as it was given to him by his father. The God became angry and he sent out heat waves to the banana. As he felt hot he removed his skin and slept on the red pillow….”

Moral: Absurd stories as well as stories with logic would invite questions from children. Be careful.

“The story can go on,” Manjunath says. “In many ways…in many forms…in many shapes,” he adds.

However, the artist is not away from logic. In South India the icons of Gods are mostly done in blue. Krishna is referred to as the Blue God. Manjunath likes Krishna. He is always there at his studio. And the icons of the Gods are covered with red silk. Memories of a ritualistic past and the daily reminders from kitsch.

Stories often start with “Once upon a time…..” and mostly end with “Then they lived happily ever after.”

Through allegories (here absurdity itself as allegory) social norms are conveyed to a young audience, who first encode and then decode the moral implications of the stories. In each phase of life, stories from the past come back to awaken one to consciousness. The co-creative process of story telling becomes a virtual continuum.

‘Once upon a time’ sets the tone of the story. It serves two purposes: One casting the listener away from the real time. Two, providing the viewer with a space of detachment from where he/she could see the truth value of what is being narrated.

For a child of Manya’s age, moving away from the real time is a fun voyage. Perhaps, a child constantly converts the real time into fantasy time. If so how does a child imagine a God or a king, when the father tells her, “once upon a time there was a god/king.” Children who are not invested with a vast visual vocabulary might envision a king from the verbal narrative provided to them and they could even imagine a king in the form of a beggar, who perhaps is familiar to them, with attributes that corresponds to a king; like beard, a head gear, a staff, sharp eyes, long hair, flamboyant/decadent dress etc.

For a child, truth value of an allegory comes from indoctrination of ideas through repeated narration. They are receptive of repetitive narratives. What Manjunath does here is a subversion of indoctrination. His defilement of the logic of grand narratives (even those of the quasi-allegories that he himself creates) and his attempt to leave them open and never ending, then functions as an advanced aesthetic strategy to destabilize the structures of linguistic patterns ingrained in the consciousness of the general art viewer. He says, “This is not even a Foucault.”

Moral: Don’t get carried away by grand theories on art. There is something very simple that looks very complex in art.

The statement of the artist, ‘This is not even a Foucault’ reminds the reader of Michel Foucault’s linguistic deconstruction using Rene Magritte’s painting ‘This is not a Pipe.’ In the art his+story Foucault’s formulation, this is not a pipe has gained an allegorical status by now. Manjunath, in his stories keep inventing allegories through the absurd interpretation of stories that have already become the collective cultural capital of a population.

Allegories have a special quality. They renew themselves to the context of its reading. They look like containing eternal truisms. Whether it is Aesop’s Fables, Panchatantra or John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress one could see morals and lessons applicable in ordinary human situations. For example:

Once upon a time, there was a software engineer who used to develop programs on his Pentium machine, sitting under a tree on the banks of a river.

He used to earn his bread by selling those programs in the Sunday market. One day, while he was working, his machine tumbled off the table and fell in the river. Encouraged by the Panchatantra story of his childhood (the woodcutter and the axe), he started praying to the River Goddess. The River Goddess wanted to test him and so appeared only after one month of rigorous prayers. The engineer told her that he had lost his computer in the river. As usual, the Goddess wanted to test his honesty.She showed him a match box and asked, "Is this your computer?" Disappointed by the Goddess' lack of computer awareness, the engineer replied, "No."She next showed him a pocket-sized calculator and asked if that was his. Annoyed, the engineer said "No, not at all!!" Finally, she came up with his own Pentium machine and asked if it was his. The engineer, left with no option, sighed and said "Yes." The River Goddess was happy with his honesty. She was about to give him all three items, but before she could make the offer, the engineer asked her,"Don't you know that you're supposed to show me some better computers before bringing up my own?"The River Goddess, angered at this, replied, "I know that, you stupid idiot! The first two things I showed you were the Trillennium and the Billennium, the latest computers from IBM!" So saying, she disappeared with the Pentium!!!Moral: If you're not up-to-date with technology trends, it is better keep your mouth shut and let people think you're a genius, than to open your mouth and reveal u r dumb!!! *

Manjunath enjoys creating allegories in his paintings and even in the performative act of telling stories out of these paintings. He profusely adopts and refashions the images and projects them into a new field of image permutations and combinations. This process of collecting and rearranging images from the vast cultural storage is like curating an archive. Manjunath calls his images as archival images; the archive that he has created in his own large scale paintings.

“What is an archive, Papa?” asks Manya.

This question cannot come from a two year old toddler. But in story there cannot be any counter questions. It is an area for suspending disbeliefs willingly.

“An archive is a renewable and ever growing collection of information. It refers to a collection of records, and also refers to the location in which these records are kept. Archives are made up of records which have been created during the course of an individual or organization's life. In general an archive consists of records which have been selected for permanent or long-term preservation.”

Manjunath actively debates the issue of preservation of images. For him images are to be used in multiple ways to create new situations which obviously would demystify the sanctity attributed to the preserved images. One could see the image of a clown cap and a politician’s cap sitting on the top of a table without disturbing eachother’s existence. But the very silence of these images generate a smile. Archival images loose their sanctity at various levels in Manjunath’s works.

Moral: Don’t discount a child because Child is the father of man.

Politics and mundane situations play a major role in the production of images and stories in Manjunath’s works. As usual he uses his inverse logic to interpret them as stories frozen in frames.

During the time of Taliban unrest in Afghanistan, one of the Indian writers** proposed an easy solution for all the problems in that country.

“In a male dominated society like Afghanistan, women do all the menial works. These Taliban soldiers who wage war during day time must be going home for food and sex during nights. The best way to solve the Taliban problem is to send the Afghan women to warfronts. When the Taliban males come to know what is child caring and cooking, they will naturally call back their women from warfronts and mend their ways.”

It is a stretched logic and this kind of logic has its own fun. They apparently look like providing a solution for any problem though a second thought reveals that they are only stretched imaginations. However, they offer a possibility to engage the brains in a different direction. Held against an evading solution, possibility for multiple solutions is always appreciable.

Manjunath’s paintings with stories or stories with paintings, in this way offer many possibilities for finding solutions for any social problems. They look real at one stage, cynical at another and eventually they look like parables that soothe the human mind but actually do not function as a solution.

Tiger and deer drinking water from the same river is an image that emphazises the ultimate expression of co-existence. It is a stretched possibility. Manjunath reformulates the image in a contemporary situation of world politics. Here one finds a cat and mouse, sworn enemies for eons, drinking milk from the same pot. They are in a cartoon situation. They can assume their real selves at any time. This is a moment of temporary reconciliation, espeically when both of them have enough to eat or drink.

“When will they start fighting again, Papa?” asks Manya.

“They will be fighting soon and the rat will make a nose dive into a soft pillow. The cat will get into the gown sleeves of the queen while the rat will try to go up through her frock,” Manjunath says.

Each picture offers a story, whose narrative could begin from anywhere and the more the viewer/artist’s dexterity the better he can take it to all narrative possibilities. Manjunath locates a story while adding qualities to an image. He feels that the moon is so soft that one should be using a pair of scissors with velvet covers for its blades, while cutting the moon into two.

“Why do you want to cut the moon, Papa?” Manya does not ask.

Because in her father’s stories every thing is possible. There is magic in Papa’s stories.

Magic is the art of hiding and revealing. Magical realism is a literary technique to hide and reveal truth in a simulated historical context. Manjunath uses both magic and magical realism in his works.

Animal forms mutate themselves to create a new reality. Static images are animated as if they were moved by some invisible forces. The curio objects placed in glass bottles start moving as if they were in a fun park. A landscape appears itself as a ‘piece’ of landscape on a wall stand. An elephant makes a careful descending through a sloppy platform without knowing that the rope that has been holding him is at the verge of a snap.

Everything is animated in this world of story objects. And the animation is materialized through the placement of images within the pictorial format. Most of them either exit or enter the picture frame from a nowhere. At times, one could see a dog partially within the frame, while its tail is on fire. One could imagine, what would be happening next?

Negation of what is socially accepted makes Manjunath’s works more interesting. The famous HMV dog is seen sitting against the gramophone. He does not want to follow His Master’s Voice. But the gramophone is not challenged. It also turns it face away from the dog. ‘I am not interested to talk to you.’

Moral: All dogs are not interested in listening to His Masters Voice.

The artist follows the child’s logic, though he likes to defy logic altogether.

“What do you do when you are tired, my sweetie?” He asks his daughter.

“I take rest, Papa,” Manya replies.

“What should an ancestral clock do if it is tired?”

“It should take rest, Papa.”

“That’s why in this painting, sweetie, you see the key is taking rest inside the belly of the clock.”

“Papa, what is this balloon doing here?”

“Sweetie, it is tired. It is breaking a wind and unwinding itself.”

Moral: If you are tired, unwind and if possible break a wind.

Manjunath’s world is full of pun and fun. He lampoons the social hypocrisy by painting the middle class aspirations objectified in three piece suits, tiger skin and souvenirs. If you take pride in having a pet Dalmatian or a tiger cub, you can sport even a collar that simulates the skin colour of the pet. Impossibilities are made into possibilities in his quirky world of stories.

The artist envisions a world where communication becomes almost impossible thanks to redundancy of certain things which are commonly in use now.

“What is that, Papa?”

“It is a cow daughter.”

“A cow, what is that?”

“A cow is an animal that gives milk.”

The child identifies milk with a feeding bottle. But it cannot identify a cow. There could be a day, when cows are seen only in pictures. Then what will the artist do?

“I paint a cow table. A table with cow legs and an udder fitted underneath it. You may even see a calf in a small table just below the udder.”

Moral: Extinction of word images from the common parlance can bring forth neo-surrealist art.

Manjunath has the last laugh as he paints ants all over the conventional images. They are going to be invaded by ants. It is an insect infested world. They would rule the world one day. The story of apocalypse is told to a little child in subtle terms.

“Who is that man, Papa?” Manya asks.

“He is a saint, baby. Look at him. He has a halo fitted behind his head. It can work as a halo when disciples are around and as a fan when he is attacked by mosquitoes.”

“Papa, will you give me this picture?”

“No my sweetie, it is already booked by an art collector.”

Moral: Children would demand saints as they think saints are like children.

JohnyML, a contemporary of Vatsyayan who wrote Kamasutra, overheard the conversation between Manjunath Kamath and his daughter Manya, and did this text thinking that it would be included in the catalogue of the show titled ‘One Hundred and Eight Stories.’